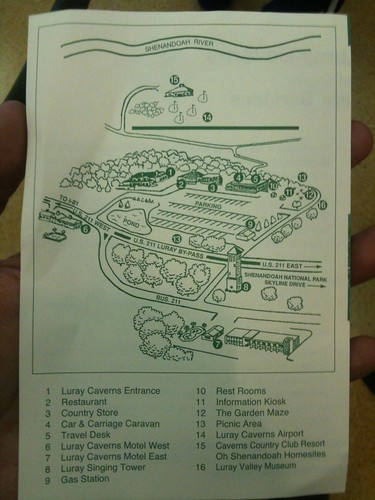

A couple of weekends ago, we visited Luray Caverns, the largest and most popular of Virginia’s many commercial show caves. Luray is about 90 miles west of DC, just off the junction of Routes US340 and US211. The drive there took about an hour and a half.

Thoroughly commercialized through the course of its history, Luray Cavens today resembles a strip mall: shops, attractions, and amusements surrounding a huge parking lot. In the early 20th Century this was also the site of “Limair Sanatorium,” a tuberculosis hospital whose cure took the form of air conditioning by a fan pulling air of “perfect bacteriologic purity” from the caverns below. The Sanatorium is gone now, destroyed in a fire and replaced by this stone-and-brick building which holds the visitor center, ticketing booth, gift shop, and the entryway to the caverns.

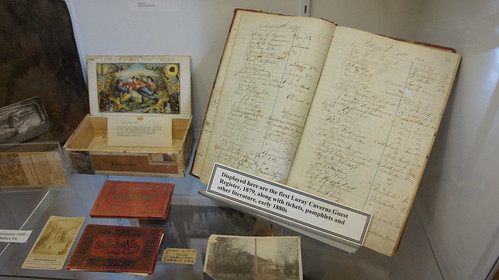

Tickets go for $24 (50% off one ticket with a Giant bonus card), which gives you access to the cave tour, along with the Car and Carriage Caravan and Luray Valley Museum. The caverns themselves are of course the chief attraction. Entry to the underground is through an inconspicuous door in a corner between the ticket booth and the gift shop. While waiting in line, guests can view an exhibit of artifacts from Luray’s history, back to its discovery in 1878.

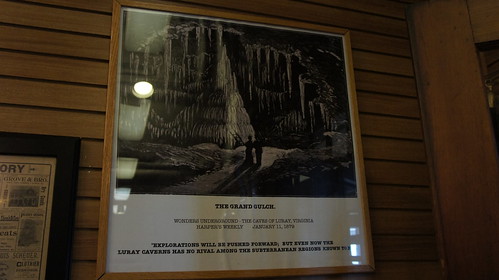

Through the door, a stair cut through the rock descends to the caverns, where a guide meets the group beside a formation named for George Washington. Looking back up the stair, a sign marks the original discoverers’ entryway into the caves.

The tour runs for about a mile and a quarter of casual walking, through caves paved with walkways and ramps of brick and concrete. Notable formations are given picturesque and evocative names like “Fish Market,” “Titania’s Veil,” “Saracen’s Tent,” “Totem Poles,” “Pluto’s Ghost,” “Shaggy Dog,” and such. The cave walls and ceilings are dense with varied stalactites and other speleothems, and brightly lit with electric bulbs covered with shades designed to blend into the rock.

There are two major bodies of water here. One is Dream Lake, a pool with a low ceiling and calm, clear water that flawlessly reflects the stalactites above, creating an illusion of depth and symmetry that belies the pool’s actual shallowness.

The other water feature is the “Wishing Well,” named and purposed for the sad but unavoidable tourist habit of throwing coins into natural formations. Perfectly clear water, lit from below and viewable from a raised walkway, reveals rocks coated with coins, and even an occasional dollar bill. (Twice a year, the pool is drained, the coins collected, and the proceeds donated to local charities.)

And then there is the Great Stalacpipe Organ, an epitome of early 20th Century “man versus nature” dominionism. An organ console controls a series of solenoids which activate hammers affixed to carefully selected stalactites, many of which were sanded down to the right pitch. With the strike of a hammer, the stalactite rings like a piano wire, and the sound is amplified, both electronically and by the resonance of the cave itself, creating ethereal tonal reverberations. (The organ is set up to autoplay Ein Feste Burg at the push of a button, but a lot of notes seem to be missing. I may have been standing in a bad part of the cave for listening.)

I’m both awed at the musical and engineering ingenuity of the organ, and shocked that anyone thought it would be okay to actively damage ancient geological marvels for the sake of music. Of course, the whole cavern floor had already been paved, and wiring strung through the walls and chasms to light up the chambers, and various formations chopped off to make room for walkways, and a whole pool designated for coin throwing; so really in the grand scheme of the caverns, a few solenoids strapped to stalactites form only the least part of the invasive approach to geology here.

Some of the broken stalactites do make for interesting cross sections.

Somewhere toward the end of the tour are the famous “fried egg” speleothems, smaller than I expected, sitting to the side of a narrow walkway through a low-ceilinged passage. They look more like oysters on the half shell to me.

The tour ends, of course, in the gift shop. Souvenirs, magnets, t-shirts, and “Official Explorer” hard hats for kids.

We have lunch in the Stalactite Cafe beside the visitor center. Mostly standard Sysco fare, but I do find the pulled pork sandwich pretty good with some nachos and cheese.

We also visit the Car and Carriage Caravan to look at some old vehicles. There’s a Conestoga Wagon here, probably crawling with dysentery and snakebite. Every old car is an impressively preserved artifact of the early auto age.

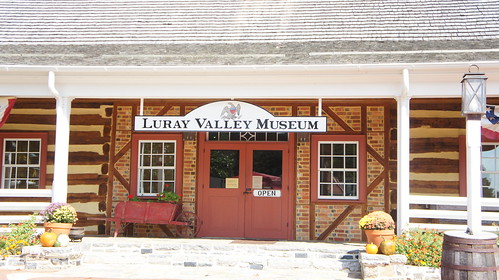

Across the street is the Luray Valley Museum, also included in admission. There are some really fascinating carved iron stove plates with biblical and mythical scenes on them, and also a butter churn powered by a dog treadmill. And another wagon.

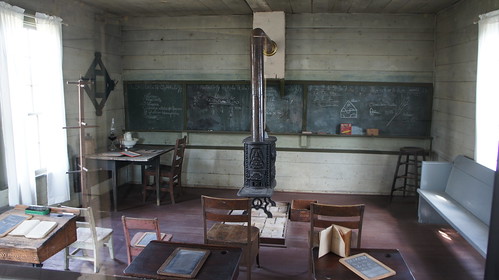

The Luray Valley Museum also includes a few restored historic structures, among them the first school for black children in the Shenandoah, and an old Mennonite meeting house.

On the way back to the car this scene burns itself into my memory: the minivans on the parking lot, the Luray Caverns gas station at the exit to the highway, the Singing Tower with its carillon of bells, backdropped by the Shenandoah Valley and the Blue Ridge. Something about it just seems so quintessentially modern-American. Especially the minivans and gas station.

Before we leave for home we drop by the gift shop one more time, and I buy the one souvenir magnet I can find in the store that says “Made in the USA” rather than China.

More photos and links: