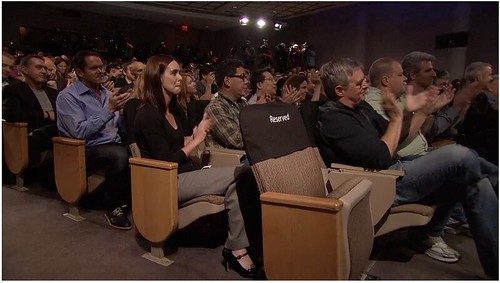

Steve Jobs died on October 5th, shortly after the iPhone 4S was announced. Jobs’ reserved seat sat empty at the event, and as new Apple CEO Tim Cook delivered the keynote he almost certainly knew the time was near. I half-expected that he would demo the new iPhone’s FaceTime app with a call to to Jobs in his sickbed, but that would probably have been a bit crass, with Jobs in no condition to deal with a video call.

Jobs didn’t invent the personal computer, laptop, graphical user interface, portable music player, smartphone, or DVR; but he did bring to all these a distinct mix of discovered design talent and business/operations acumen that transformed average consumer electronics into accessible life-changing devices, defying expectations and thinking so future-forward that sometimes it seemed crazy. From a $666.66 DIY motherboard kit, to touchscreen communications devices made from tiny logic boards strapped to giant batteries, Apple under Jobs managed to take existing ideas, introduce to them a magical sense of aesthetically rewarding utility, and sell them on a Reality Distortion Field-powered cloud of overwhelming cultural desirability. I was not immune.

Some final notes: His sister’s eulogy, the Apple memorial page, and the naturopathic folly Jobs held to that allowed his cancer to progress past the threshold of survivability.

Steve Jobs’ death was shortly followed by the deaths of Dennis Ritchie and John McCarthy, arguably even greater computer giants for their own seminal contributions. Ritchie created C and helped create UNIX, while McCarthy created Lisp and influenced the development of artificial intelligence. Their deaths made less of a public splash than Steve Jobs’, but their technological legacies deserve as much memorialization and reflection.

There have been analogies to Edison, but I like to rank Jobs and Ritchie and McCarthy more along the lines of Babbage, Lovelace, Morse, Turing, and other past luminaries upon whose shoulders the current computer age stands.