On July 14th, the NASA/JHUAPL spacecraft New Horizons flew by Pluto, nine years after its launch. Traveling too fast to slow down into orbit, New Horizons zipped past Pluto and its moons with cameras and sensors intensely trained on them to gather science and imagery, then turned around to beam the data back to earth over weeks and months to come, while piercing farther into deep space to explore the outer solar system.

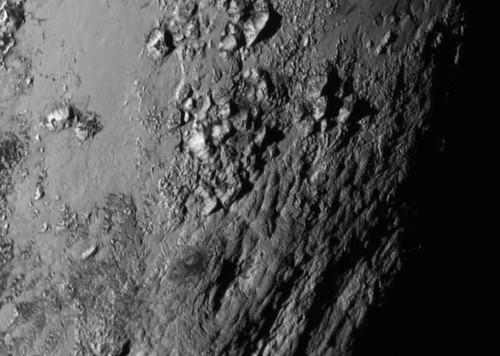

Pluto, it turns out, is a stranger world than we thought: tinted beige by hydrocarbons, adorned with a giant heart-shaped feature (dubbed Tombaugh Regio after Pluto discoverer Clyde Tombaugh) sporting mountains of frozen methane and carbon monoxide thrusting up from a young, un-cratered surface, all wrapped in an expansive atmosphere of rarefied nitrogen. Pluto and its moon Charon seem geologically active and surprisingly varied, a far-flung cryo-geo-chemical mishmash that is worth additional exploration, along with other potentially more fascinating worlds in the Kuiper Belt and outer solar system.

It’s a long, slow trip for the data gathered by New Horizons: 4.5 light-hours at 1-4 Kbps, so new images and observations from that short flyby interval will be trickling down for a while yet.

Also, Tombaugh Regio might not be a heart.

The best thing about the Pluto image from NASA today is the silhouette of Pluto the dog right on it. pic.twitter.com/hVqD5QTwGz

— Scott Johnson (@scottjohnson) July 14, 2015

More from the JHUAPL Pluto site, which will update constantly over the course of the next year or so as more data trickle down from the New Horizons spacecraft.

Also see How Pluto’s most spectacular image was made—and nearly lost, and some commentary from Wired on NASA’s social media strategy for the Pluto Flyby — most notably the exclusive preview on Instagram.